SOUHRN

Arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy of the right ventricle of Boxers (ACPKB) is one of the diseases observed in the breed. ACPKB is one of the primary cardiomyopathies with a genetic cause. The disease is similar to that of humans. It is a disease with clinical manifestations in adulthood. Three forms of the disease are described: hidden, overt and a form with myocardial dysfunction. Diagnosis is based on family history, presence of ventricular arrhythmias, history of syncope or exercise intolerance. A genetic test has been developed. Therapy is based on the form of the disease detected. Many boxers with this disease are at risk of sudden cardiac death. Keywords: arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy, boxer, Holter ECG, ventricular premature complexes.

Arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy of the right ventricle of Boxers (ACPKB) is one of the diseases observed in the breed. ACPKB is one of the primary cardiomyopathies with a genetic cause. The disease is similar to that of humans. It is a disease with clinical manifestations in adulthood. Three forms of the disease are described: hidden, overt and a form with myocardial dysfunction. Diagnosis is based on family history, presence of ventricular arrhythmias, history of syncope or exercise intolerance. A genetic test has been developed. Therapy is based on the form of the disease detected. Many boxers with this disease are at risk of sudden cardiac death. Keywords: arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy, boxer, Holter ECG, ventricular premature complexes.

Home

There are three heart diseases in Boxers that are monitored in breeds of this breed. These diseases are subaortic and pulmonic stenosis, dilated cardiomyopathy and arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy of the right ventricle of the heart in Boxers (ACPKB). AKPKB is also often referred to as boxer cardiomyopathy (Broschk, 2005; Jenni, 2009; Meuers, 2004). AKPKB is known by the acronym ARVC from the English Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy. In subaortic and pulmonic stenosis, the inheritance is unknown and polygenic inheritance is considered. Dilated cardiomyopathy has an unknown genetic etiology as in other breeds. ACPKB is inherited as an autosomal dominant disease with incomplete penetrance.

Myocardial disease in boxers was first described by Dr. Neil Harpster in the early 1980s. On careful examination, it was found that cardiomyopathy in boxers resembles myocardial disease in humans - the so-called arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (RVCC). The similarity is in clinical presentation, pathological findings and likely aetiology. ACPK in humans is an inherited heart muscle disease characterized by infiltration of the right ventricular wall by adipose and fibrous-fatty tissue. Ventricular tachycardia and arrhythmias are evident on ECG. Affected individuals are at risk of sudden cardiac death. (Meuers,2004).

The classification of cardiomyopathies is based on the definition of cardiomyopathy published by the American Heart Association in 2006. "Cardiomyopathy is a heterogeneous group of myocardial diseases that are associated with mechanical and/or electrical dysfunction. They usually exhibit inadequate ventricular hypertrophy or dilatation and result from a variety of causes that are often genetic. Cardiomyopathies may manifest only in the heart or are part of an overall disease, often leading to cardiovascular death or progressive heart failure." Right ventricular arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy is a primary cardiomyopathy (affecting the heart muscle directly) with a genetic cause (see Table 1) (Kvapil, 2008).

Table 1: Proteins and genes causing ACPK in humans

| Protein | Gen |

|---|---|

| Ryanodine receptor type 2 | RYR2 |

| Laminin receptor | Lamr1 |

| LBD3 (Cypher/ZASP) | Lbd3 |

| Desmoplakin | Dsp |

| Plakophilin 2 | Pkp2 |

| Desmocollin 2 | Dsc2 |

| Cellular plakoglobin | Yup |

| Plakoglobin | |

| Desmoglein 2 | DSG2 |

| Transmembrane protein 43 | TMEM43 |

Pathological changes

Pathological examination of the hearts of boxers with ACCP revealed right ventricular dilatation in 35 % dogs (8 of 23). Histopathological changes were found in all dogs and were very similar to those in humans with AKPK. Replacement of right ventricular cardiomyocytes by adipose or fibrous tissue was most commonly found. On this basis, two forms can be distinguished: the fatty form (15 boxers, 65 %) and the fibrous-fatty form (8 boxers, 35 %). In 48 % (11) dogs, the same lesions were found in the wall of the left ventricle, and in 35 % boxers (8), the walls of the left and right atria were affected. Myocarditis characterized by lymphocytic focal or multifocal infiltrates was found in the right ventricle of 61 % Boxers (14). In 70 % dogs (16), nonpurulent myocarditis affected the left ventricular wall. Myocardial apoptosis was found in 39 % dogs (9). Myocarditis and fibrous-fatty myocardial involvement were characteristic of boxers with ACCP that died suddenly (Basso, 2004).

Clinical picture

It is a disease with clinical manifestations in adulthood. In some individuals, changes on the Holter ECG and clinical symptoms may not appear until the age of six.

It is a disease with clinical manifestations in adulthood. In some individuals, changes on the Holter ECG and clinical symptoms may not appear until the age of six.

Affected individuals may die suddenly as a result of lethal ventricular arrhythmias, or develop symptoms of congestive heart failure due to systolic dysfunction, or may live an asymptomatic life. The disease primarily affects the electrophysiological properties of the myocardium.

Three forms of the disease are described: hidden, overt and a form with myocardial dysfunction. The hidden form is characterized by asymptomatic dogs with occasional ventricular premature complexes (VPC). The overt form is characterized by dogs with tachyarrhythmias and syncope or exercise intolerance. The least frequently diagnosed form is the third form, which is associated with diastolic myocardial dysfunction and sometimes with signs of congestive heart failure. (Meuers, 2004)

Out of 239 dogs, 23 boxers were diagnosed with ACPKB. Arrhythmias of ventricular origin noted on 24-hour Holter ECG were premature ventricular complexes in 19 dogs (83 %) and ventricular tachycardia in 11 dogs (48 %). Clinically, syncope was noted in 12 Boxers (52 %). Of these 23 boxers, 3 (13 %) were euthanized due to severe and drug-resistant heart failure, 9 boxers (39 %) died suddenly, and 11 boxers (48 %) died or were euthanized for other reasons (Basso, 2004).

Diagnostics

Diagnosis is based on the presence of a combination of factors. These factors are family history, history of ventricular arrhythmias, history of syncope or exercise intolerance, and postmortem findings of fibrous and fatty infiltration in the myocardium. In 2007, veterinary cardiologist Meuers of Washington State University described the gene that causes AKPK in boxers and developed a test to detect the mutated gene. However, further work needs to be done to verify if this mutation is the only one that causes AKPK in boxers or if there are other mutations causing the disease (Meuers, 2009). The above genetic test can be ordered from the Washington State University website - http://www.vetmed.wsu.edu/deptsVCGL/Boxer/index.aspx .

Clinical examination

Most dogs have normal clinical findings. In some dogs, auscultation may detect a pulse deficit. A heart murmur, most commonly an audible left apical murmur, may be indicative of myocardial dysfunction. However, we must be cautious when assessing cardiac murmurs in boxers because many adult boxers have a murmur auscultated over the left cardiac base, which may be physiological or in some cases associated with subvalvular or valvular aortic stenosis (Jenni, 2009).

Electrocardiography

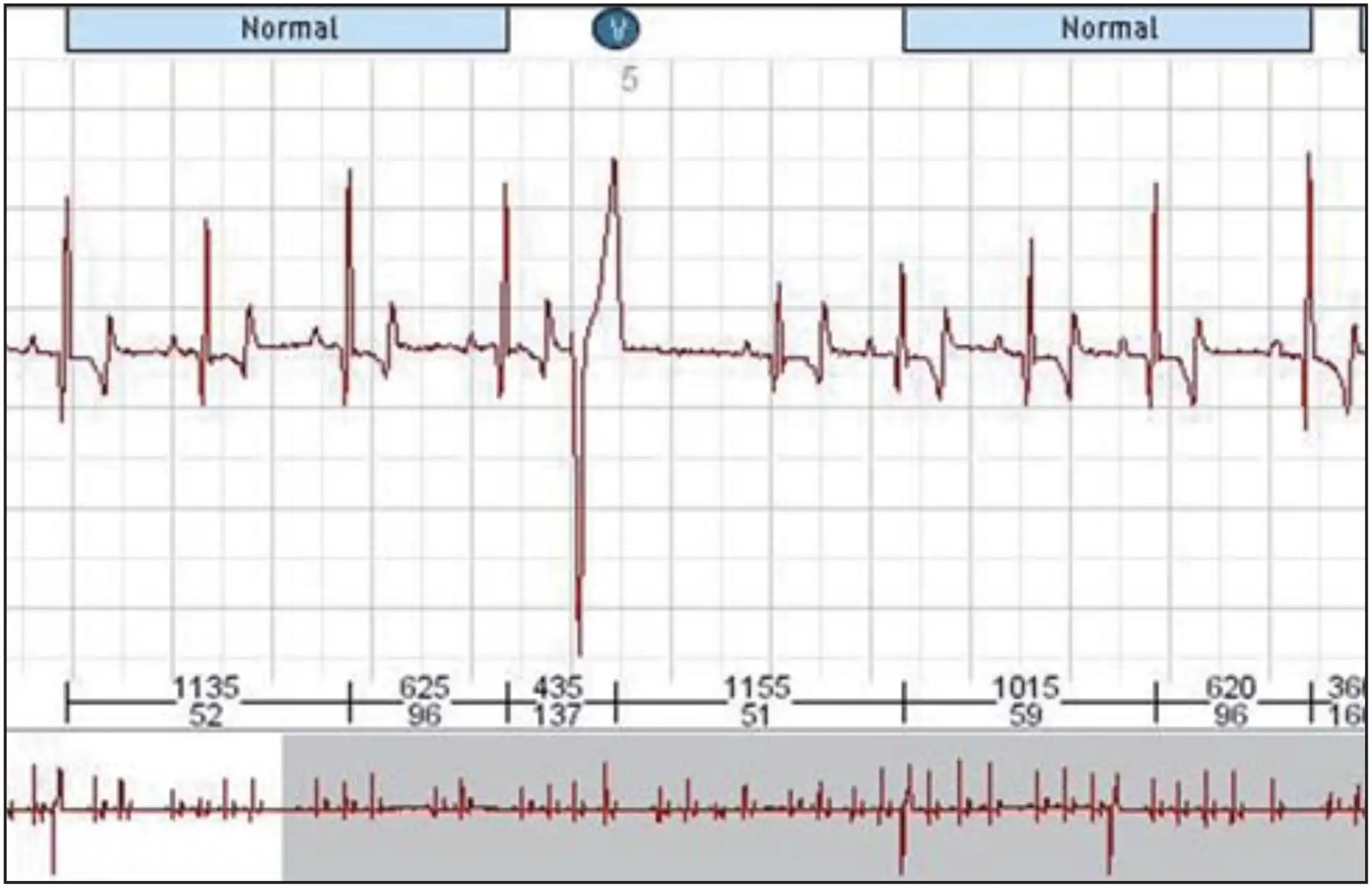

Affected dogs may have increased ventricular ectopy, but this may be intermittent. The presence of CPK is suggestive of disease. However, a normal ECG does not exclude the diagnosis of ACCP because the arrhythmia is intermittent. If an arrhythmia is detected auscultation and clinical signs (syncope, exercise intolerance, family history of disease) are present, a 24-hour ECG (Holter examination) is indicated. Examination of dogs older than 3 years has been recommended and should be repeated annually (Meuers, 2004).

Temporal variability in the occurrence of ventricular arrhythmias during the day has been described in 162 boxers with ACCP. A total of 1181 Holter ECG recordings from 1997 to 2004 were compared. The likelihood of occurrence of ACCP in the Xers was relatively constant during the day, although slightly higher between 8 am and 12 pm and between 4 pm and 8 pm (Scansen, 2009).

Holter ECG examination

This examination is an important part of the diagnosis, screening and therapy control of ACPKD. Holter ECG examination allows better assessment of the frequency and complexity of the arrhythmia and is an important component for monitoring therapy. Premature ventricular extrasystoles also occur in healthy dogs. An assessment of more than 300 asymptomatic adult Boxers found that 75 % of the population had less than 75 CPKs in 24 hours. Therefore, the finding of more than 100 CPKs in 24 hours in an adult boxer strongly suggests a diagnosis of ACCP, especially when arrhythmia complexity (couplets, triplets, bigeminy or ventricular tachycardia) is present (Meuers, 2005).

In some cases, however, the Holter examination may be negative and yet ACPKD is suspected on the basis of clinical symptoms. This is due to the day-to-day variability of arrhythmias in affected dogs. Untreated boxers with ACPK have more than 83% day-to-day variability in the number of KPKs (Meuers, 2004).

Echocardiography

Although ACCP is a myocardial disease, most myocardial changes are abnormalities noted only on histological examination. Therefore, most affected dogs have a normal echocardiogram. In some cases, right ventricular enlargement and sometimes right ventricular dysfunction may be noted.

Troponin and natriuretic peptide testing

Boxers with ACCP have a significantly increased serum concentration of cardiac troponin I (cardiac troponin I cTnI). A correlation has also been found between cTnI levels and the number of CPK/24 hours (Baumwart, 2007).

There was no significant difference in brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) concentration between boxers with ACCP and healthy boxers. BNP is not an indicator of AKPK in boxers (Baumwart, 2005).

Screening

The introduction of the genetic test makes screeing easy, but we must remember that it is not known exactly whether only one mutation is the cause of ACPK in boxers. Therefore, Holter ECG examination remains the investigative method used in the screening of ACE in boxers. ACPKD is a disease with onset of clinical symptoms in adulthood and the degree of ventricular ectopy increases with age. Therefore, a single Holter ECG performed at a young age in a dog may not reveal an affected animal. Therefore, annual Holter ECG examination is recommended. There is no strict relationship between the development of symptoms and the number of CPCs. Although syncope in these patients tends to be associated with a greater number of CPCs and a greater degree of complexity. The following screening evaluation of Holter ECG in Xers has been proposed (see Table 2) (Meuers, 2004).

Therapies

Therapy for affected dogs usually consists of administering antiarrhythmic drugs only, as most affected dogs do not have systolic dysfunction. After starting antiarrhythmic therapy, a repeat Holter ECG should be performed in 2 to 3 weeks. An 80% reduction in the number of CPCs as well as a reduction in arrhythmia complexity is considered a positive response to therapy (Meuers, 2004).

Asymptomatic boxers

It is not yet well known when to start therapy in asymptomatic boxers. Some boxers die due to arrhythmia before they show clinical signs. Persistent ventricular tachycardia (longer than 30 seconds) is a risk factor for sudden death in humans. Also, CPK that occurs in early diastole, an R to T phenomenon, is dangerous. Therefore, it is recommended that therapy be initiated in patients who have more than 1000 CPK /24 hours, episodes of ventricular tachycardia, or evidence of R to T phenomenon (Meuers, 2004).

Boxers with syncope and exertion intolerance

The ideal condition is to start therapy only after a Holter ECG examination. A reduction in the number of CPCs and arrhythmia complexity occurred with the two protocols described. The first involves the administration of sotalol (1.5-2.0 mg/kg over 12 hours). The second is the administration of a combination of mexiletine (5-8 mg/kg after 8 hours) and atenolol (12.5 mg for this after 12 hours).

Boxers with ventricular dilation and systolic dysfunction

In these cases, the same therapy is recommended as for dilated cardiomyopathy.

Administration of fish oil seems to be a suitable complementary therapy. Its administration for 6 weeks to boxers with ACCP has been found to reduce arrhythmia. (Smith, 2007) Fish oil can be administered at a dose of 40 mg/kg EPA (eicosapentaenoic acid) and 25 mg/kg DHA (dodecahexaenoic acid) (Meuers, 2005).

Forecast

Dogs with ACPKB are always at risk of sudden cardiac death. Many sick dogs live their entire lives without therapy, also medicated dogs can live their entire lives without symptoms. A small percentage of dogs develop symptoms of chronic heart failure, which is associated with ventricular dilation and systolic dysfunction

Conclusion

Arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy of the right ventricle of Boxers (ACPKB) is one of the heart diseases that occur in this breed. The disease is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern with incomplete penetrance. A genetic test has been developed to help detect affected individuals and can serve as a selection criterion in Boxer breeding. Diagnosis of ACPKB is based on family history, presence of ventricular arrhythmias, history of syncope, exercise intolerance and typical histopathological findings.

Mutations in other genes that cause ACPKD remain a question. Therefore, Holter testing remains the test to detect individuals affected by ACPKD. This examination also allows the success of antiarrhythmic therapy to be assessed.

MVDr. Roman Kvapil

Veterinary ambulance

Dürerova 18

Prague 10

Literature

- Basso C et al. Arrythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy Causing Sudden Cardiac Death in Boxer Dogs: A New Animal Model of Human Disease. Circulation 2004;109:1180-1185

- Baumwart RD et al. Assessment of plasma brain natriuretic peptide concentration in Boxers with arrythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Am J Vet Res, 2005;66(12):2086-9

- Baumwart RD et al.Evaluation of serum cardiac troponin I concentration in Boxers with arrythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. AmJ Vet Res. 2007;68(5):524-8

- Broschk C et al. Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) in dogs-pathological, clinical, diagnosis and genetic aspects. Dtsch Tierarztl Wochenschr. 2005;112(10):380-5

Corrado D et al. Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy/ Dysplasia: Clinical Impact of Molecular Genetic Studies. Circulation 2006;113:1634-1637 - Jenni S et al. Use of auscultation and Doppler echocardiography in Boxer puppies to predict development of subaortic or pulmonary stenosis. J Vet Intern Med.2009;23(1):81-6

- Kvapil R. Cardiomyopathy and genetics - review. Veterinary medicine 2008;58:438-447.

Meurs KM. Boxer dog cardiomyopathy: an update. Vet Clin Small Anim 34(2004), 1235-1244 - Meuers KM. Right ventricular arrhythmic cardiomyopathy: An update on Boxer cardiomyopathy. The North American Veterinary Conference - 2005 Proceedings, 122-123

- Meuers KM et al. Genome-wide association identifies a Mutation for Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy in the Boxer dog. ACVIM Forum, 2009, Abstract, J Vet Intern Med 23:687-688

- Scansen BA et al. Temporal variability of ventricular arrhythmias in Boxer dogs with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. J Vet Intern Med, 2009; 23(5):1020-4

- Smith C et al. Omega-3 fatty acids in Boxer dogs with arrythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. J Vet Intern Med 2007;21:256-273